Ok, so there’s probably no such thing as a plagiarism-proof assignment, but I think I’ve got a reasonable approximation thereof.

Ok, so there’s probably no such thing as a plagiarism-proof assignment, but I think I’ve got a reasonable approximation thereof.

It originated with my frustration with the perpetual struggle to have students in my distance education classes answer questions in their own words. My students are using their textbooks to answer questions, and many seem to feel that a textbook is the exception to the rule when it comes to plagiarism. Some simply don’t understand that they’re doing anything wrong. From experience, I can tell you that many people who are not my students also see it that way, and complaining about it is a great way to be branded as unreasonable. The problem, as I’ve documented before, is that students who copy from their textbook also tend to fail the class. After last term, I’ve decided that it’s in my best interest to consume alcohol before grading assignments. I’m not allowed to ignore plagiarism, but what I don’t see…

Absent blissful ignorance, the only way to deal with plagiarism (without causing myself a variety of problems) is to change the assignments so that plagiarism isn’t possible. Now, if you’ve attempted to do this, you know it isn’t easy. A search online will give you tips like having students put themselves in the position of a person experiencing a historical event, and explaining their perspective on the matter. That’s something students (most likely) can’t copy from the internet. But suggestions like that are not especially helpful when the topic is how volcanoes work. (Although now that I think about it, “Imagine you are an olivine crystal in a magma chamber…”)

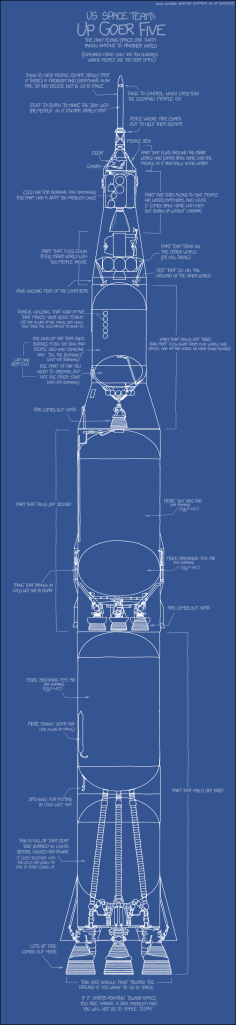

The solution came from my online source of comfort, xkcd. Randall Munroe, the creator of the webcomic, set himself the challenge of labeling a diagram of NASA’s Saturn 5 rocket (Up Goer Five) with only the 1000 most commonly used words in the English language. Soon after, members of the geoscience community took up the challenge of explaining their fields of research in the 1000 most commonly used words. Here are two examples from a blog post by hydrogeologist Anne Jefferson. Anne writes:

” So I decided to see if I could explain urban hydrology and why I study it using only the words in the list. Here’s what I came up with:

I study how water moves in cities and other places. Water is under the ground and on top of it, and when we build things we change where it can go and how fast it gets there. This can lead to problems like wet and broken roads and houses. Our roads, houses, and animals, can also add bad things to the water. My job is to figure out what we have done to the water and how to help make it better. I also help people learn how to care about water and land. This might seem like a sad job, because often the water is very bad and we are not going to make things perfect, but I like knowing that I’m helping make things better.

Science, teach, observe, measure, buildings, and any synonym for waste/feces were among the words I had to write my way around. If I hadn’t had access to “water”, I might have given up in despair.

But my challenge was nothing compared to that faced by Chris, as he explained paleomagnetism without the word magnet:

I study what rocks tell us about how the ground moves and changes over many, many (more than a hundred times a hundred times a hundred) years. I can do this because little bits hidden inside a rock can remember where they were when they formed, and can give us their memories if we ask them in the right way. From these memories we can tell how far and how fast the rocks have moved, and if they have been turned around, in the time since they were made. It is important to know the stories of the past that rocks tell, because it is only by understanding that story that we really understand the place where we live, how to find the things that we need to live there, and how it might change in the years to come. We also need to know these things so we can find the places where the ground can move or shake very fast, which can be very bad for us and our homes.”

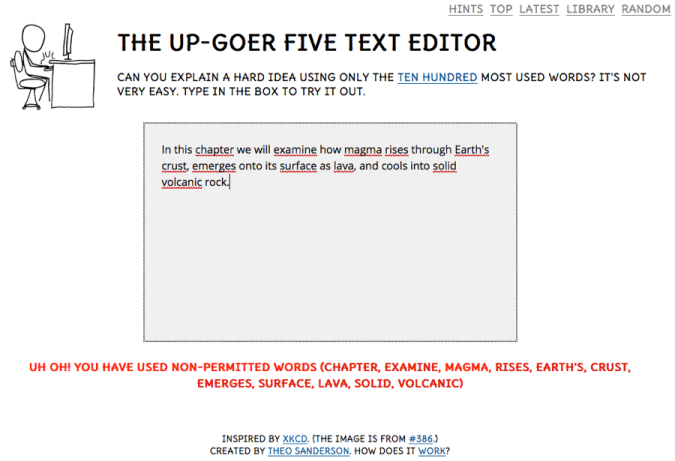

Is that brilliant, or what?! To make it even better, Theo Sanderson developed a text editor to check whether only those words have been used. This is what happened when I typed part of the introduction to the chapter on volcanoes:

I decided to test-drive this with my class. I gave them the option of answering their assignment questions in this way. It’s difficult, so they got bonus points for doing it. A handful attempted it, and that was probably the most fun I’ve ever had grading assignments. If you’d like to give this kind of assignment a shot, there are a few things to keep in mind:

- Students (and colleagues) may be skeptical. Explain that the exercise requires a solid knowledge of the subject matter (in contrast to paraphrasing the textbook) and is a very effective way for students to diagnose whether they know what they think they know. In my books, that gives it a high score in the learning-per-unit-time category.

- The text editor has some work-arounds, like putting single quotes around a word, or adding “Mr or “Mrs” in front of a word (e.g., Mr Magma). Head those off at the pass, or you’ll get “But you didn’t say we couldn’t!”

- You may wish to allow certain words for the assignment or for specific questions, depending on your goals. For example, if I were less diabolical, I might consider allowing the use of “lava.” The other reason for not allowing “lava” is that I want to be sure they know what it means. In contrast, I probably wouldn’t make them struggle with “North America.”

- Make it clear that simple language does not mean simple answers. I found that students tended to give imprecise answers that didn’t address important details. I don’t think they were trying to cut corners—they just didn’t think it was necessary. If I were to do this again I would give them a rubric with examples of what is and isn’t adequate.

- Recommend that they write out the key points of their answers in normal language first, and in a separate document, and then attempt to translate it.

- Suggest that they use analogies or comparisons if they are stuck. For example, Randall Munroe refers to hydrogen as “the kind of air that once burned a big sky bag.”

- Make the assignment shorter than you might otherwise, and focus on key objectives. Doing an assignment this way is a lot of work, and time consuming.

- And finally, (as with all assignments) try it yourself first.

In that spirit:

I like to make stories with numbers to learn what happens when things go into the air that make air hot. Very old rocks from deep under water say things that help make number stories. The number stories are not perfect but they still tell us important ideas about how our home works. Some day the number stories about how old air got hot might come true again, but maybe if people know the old number stories, they will stop hurting the air. If they don’t stop hurting the air, it will be sad for us because our home will change in bad ways.